The six-year-long conflict that was World War II colored most aspects of American life. Far from the front lines, its impact reached the kitchen, where a series of mandatory rations left American homes with limited sugar, flour, and animal fat.

Recipes for sweet, scrappy cakes abounded in newspapers and baking pamphlets. The cooking guides did double duty of instructing American women on how to make the most of their leaner pantries while also boosting morale. A widely published bedtime tale from 1918, “Uncle Wiggly and the Victory Cake,” which was syndicated in The St. Louis Star and Times, The El Paso Herald, and The Buffalo Enquirer, offered home bakers advice. “We must all help win the war,” part of the story reads. “And one way is to save sugar for the soldier boys. Make your cakes without so much sugar in them. Make them victory cakes. Put in cocoanuts or peanuts or something like that.”

Americans had been preparing for such lifestyle changes during the difficult decades between 1914 and 1939. Rationing had occurred during the first World War, too, but it was voluntary. As many Americans opted to send shelf-stable items like sugar and white flour headed abroad to feed the troops, women made “war cakes,” often sweetened with boiled raisins, a cheap, readily available dried fruit that made a capable substitute for sugar. As the hard times continued with the onset of the Great Depression, home cooks baked “wacky cakes.” The wackiness here may have been a nod to the ingenious use of vinegar, which not only brightened and leavened limited ingredients, but allowed bakers to use less flour.

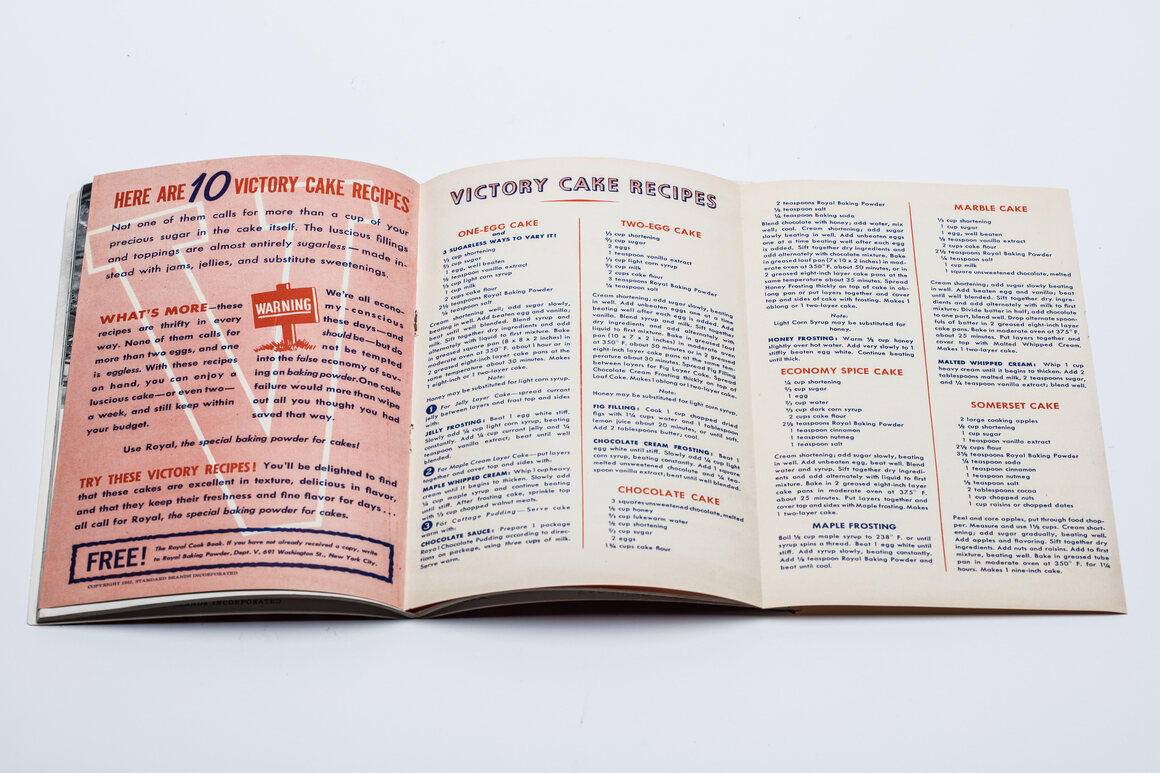

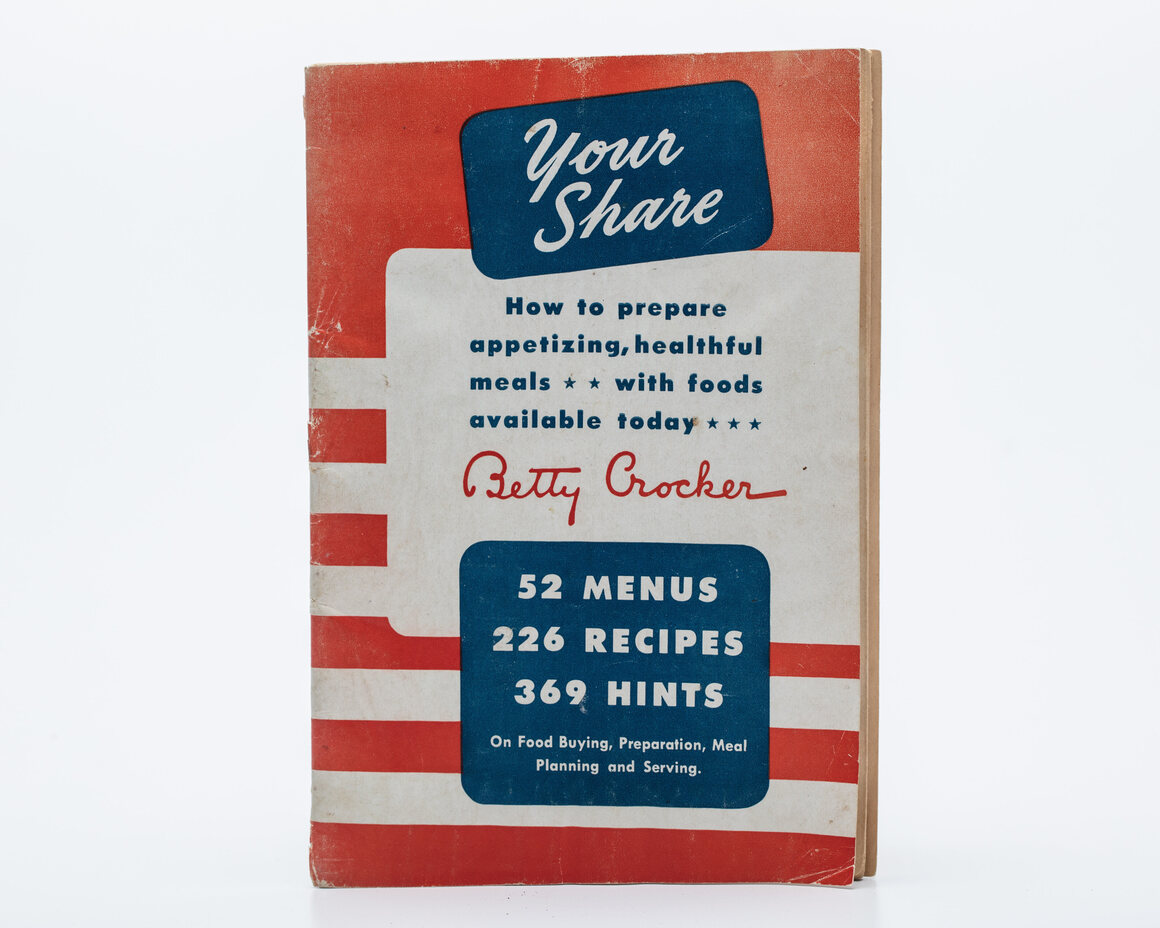

With World War II, a more inspiring terminology took hold. The war cake—like its cousin, the war garden—was rebranded by newspapers and baking companies as the victory cake. “After World War I, there’s so much negative reaction to the war, and the brutality of the war, that calling things ‘war whatever’ takes on a very negative connotation,” says food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson.

Recipes for victory cakes were directed toward female homemakers. The Low Sugar Victory Lemon Cake, for instance, published in The Morning Call in 1942, billed itself as “the housewife’s answer to the sugar shortage.” The cake substitutes “glassed sugar” (corn syrup) to bolster the cake’s sweetness. The Crisco Victory White Cake, published in The Kansas City Times in the same year, called on women to bake for their families. “Lady—your family will say you’re a magician when you serve this new mouth-melting, sugar-saving Victory Cake!” the recipe header promises.

These recipes harnessed the national mood. By 1942, the United States had enacted rations on meat and coffee, as well as on sugar and flour. By 1943, the country would suffer a butter shortage. Sugar was by far the biggest pantry commodity of the time; it was rationed from the early 1940s until 1947. And Americans were already working with a depleted stock, as access to Southeast Asian sources had dried up. “With the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, things change,” says Dr. Cynthia R. Greenlee, a historian, journalist, and senior editor at The Counter. “The currents of trade have to change, because you can no longer assume that the Pacific Coast—you know, the gateway to Asia—is going to be open for trade.”

Wartime cake baking relied on items that were more plentiful. Recipes from the time frequently summon cocoa, corn syrup, and shortening. Cocoa, according to Wassberg Johnson, was not in short supply, although Greenlee points out that chocolate was often reserved for soldiers. In fact, a 1940s-era Nestlé ad from The Saturday Evening Post encouraged Americans to stop buying the product, announcing, “Chocolate is a fighting food!” Corn syrup, says Wassberg Johnson, was produced from a domestically grown product and stored in a glass bottle that was too heavy to ship abroad. And shortening, vegetable-based, was used to replace hard-to-come-by butter. It was a shelf-stable, mass-produced, inexpensive item that near everyone could get a hold of.

Sometimes, victory cakes of the era contained eggs; other times they did not. Sometimes, the cakes contained milk; sometimes they did not. Sometimes they were more akin to spice cakes, with a raisinated base; other times, they relied on chocolate. That variability in recipes, Greenlee says, was the result of an unreliable supply chain.

What ultimately bound victory cakes of different eras together was their “make do” attitude. A cake is no luxury, these recipes say. A cake is a food anyone can enjoy, even in lean times. “It’s something that makes you happy in a very unhappy time,” Wassberg Johnson says. In times like war and the Great Depression, when “food wasn’t necessarily abundant for everybody,” dishes with sugar and starch were “incredibly craveable, and that gave comfort to people.”

The below adapted recipe for victory cake is a pantry cake, made from items that largely have no real expiration date, including coffee, which enhances the cocoa. Although coffee was rationed during World War II, it lasted only a single year, ending in 1943. This was likely due to the fact that domestic roasting also took off during the '40s and '50s, Greenlee says, meaning that coffee was a product that nearly every American could easily access.

I have also included oranges, a domestic American crop that, Wassberg Johnson says, certainly would have been available during World War II. Orange extract, which is used in both the cake and its frosting, could have been produced at home, using orange peel and grain alcohol. Vanilla extract, for its part, was commercially available in the United States beginning in the late 1800s. Candied orange peels, used in the batter and as a garnish, are a reminder of the waste-not philosophy that pulsed through wartime.

Most victory cakes lacked frosting, though icing was somewhat common. In 1942, Crisco sponsored a recipe in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram for Victory Layer Cake with Chocolate-Peppermint Icing, for instance, the primary ingredient for which is sweetened condensed milk. Frosting, in this version of a victory cake, is non-traditional, though it adds a layer of indulgence to a dessert that was, on its face, about indulging, regardless of the world’s troubles. The addition of orange is also non-traditional, though there are several interpretations of victory cakes from the time that use lemons and lemon extract. Still, this marriage of old and new is a reminder of one prevailing concept. A victory cake, made today, or tomorrow, or 80 years ago, is a cake that forces us to see beyond today. It says: We can survive all this. It says: there will always be cake.

Victory Cake

Recipe adapted from AllRecipes’ Victory Chocolate Cake

For the Candied Orange Peel:

2 large oranges, 1/4 inch of top and bottom cut off

3 cups sugar, divided

3 cups water

1. Heat a medium-sized pot of water to boiling. Cut the peel from each orange into 4 vertical parts, removing the segments and pith. Cut the peel again, into ¼-inch strips. Add the peel to the boiling water and boil for 15 minutes. Drain and rinse the peels.

2. Bring 2 cups of sugar and 2 cups of water to boil over medium heat, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Add the boiled peels and bring to a boil again. Reduce the heat and simmer the mixture until the peel is soft, roughly 30 minutes. Remove and drain. Reserve liquid and refrigerate for future use as an orange simple syrup.

3. Toss the peels with the remaining sugar on a rimmed baking sheet, pulling them apart so that they are separated into individual strands. Transfer the coated peels to a piece of aluminum foil and allow them to stand until dry, 1 to 2 days. These candied peels can be made in advance, and can hold in the freezer for up to 2 months.

For the Cake:

2 cups sifted all-purpose flour

2 ¼ teaspoons baking soda

¾ cup shortening

1 ½ cups dark corn syrup

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 ½ teaspoon orange extract

½ cup unsweetened cocoa powder

¾ teaspoon salt

⅓ cup white sugar

3 eggs

1 cup cold, brewed coffee

1 1/2 cup candied orange peels, cut into bite-sized pieces (see recipe)

1. Grease a 9” cake pan and preheat oven to 350 degrees. In a mixing bowl, sift together flour, baking soda, cocoa, and salt and set aside. Separate the eggs and beat egg whites in a large bowl until stiff peaks form. Set aside.

2. Cream together the shortening and sugar with an electric mixer until a light and fluffy mixture is formed. Add the corn syrup, egg yolks, vanilla, and orange extract. With the mixer running on medium speed, add the dry ingredients in batches, alternating with the cooled coffee. Scrape down the bowls of the mixture and make sure everything is combined.

3. Fold in the orange slices until completely incorporated. Gently fold in the beaten egg whites until just combined and pour the batter into the greased pan. Bake the cake for 40 minutes, or until a cake tester inserted into the middle comes out clean. Cool in the pan for 10 minutes and then slice around the edges with a knife and transfer to a cooling rack.

4. Once the cake has cooled completely, frost with the orange frosting, if desired. Garnish with remaining orange peel.

For the Frosting:

2/3 cup shortening

1/4 teaspoon vanilla extract

¾ teaspoon orange extract

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 cups powdered sugar

5 to 6 tablespoons fresh orange juice

2 tablespoons milk

1 tablespoon grated orange zest

1. Combine shortening, vanilla, orange extract, and salt in a mixing bowl and beat together with an electric mixer until blended.

2. Add the powdered sugar and beat on low speed, adding the orange juice and milk until well integrated.

3. Add in the orange zest and beat on high until smooth. Leave at room temperature for at least 10 minutes before using.